Epilepsy

Highlights

What Is Epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a brain disorder that is marked by recurrent seizures. Seizures (also called fits or convulsions) are episodes of disturbed brain function caused by abnormalities of the brain’s electrical activity. There are many different types of seizures.

Causes

Epilepsy can affect people of all ages but is most common in young children and older adults. Some types of epilepsy are inherited and due to genetic factors. Other possible causes of epilepsy include brain injuries such as head trauma or oxygen deprivation at birth. In many cases, the cause of epilepsy is unknown (idiopathic).

Diagnosis

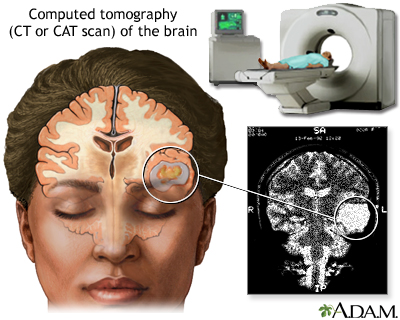

A doctor will diagnose epilepsy based on a patient’s medical history, description of seizures, and various diagnostic tools. The most important diagnostic tool is the electroencephalogram (EEG), which records and measures brain waves. Imaging tests such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used.

Treatment

The goal of epilepsy treatment is to control seizures. Many different types of anticonvulsant drugs are available to treat epilepsy. Some patients need only one drug, while others may need to take several drugs. For patients who have not been helped by medication, surgery may be an option. Dietary changes, such as the ketogenic diet, have shown promise in helping some patients, especially children with severe epilepsy.

Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) can cause many side effects. Pregnant women with epilepsy need to take special precautions, because some of these drugs (particularly valproate) can cause birth defects.

Drug Warning

In 2011, the FDA issued updated warnings on birth defect risks and AEDs:

- Valproate may have long-term effects on a child’s cognitive development if the mother takes it during her first trimester of pregnancy. Studies indicate that children born to mothers who took valproate during pregnancy had lower scores on IQ and other cognitive tests than children whose mothers took other types of AEDs. Valproate drug products include valproate sodium (Depacon), valproic acid (Depakene), and divalproex sodium (Depakote).

- Topiramate (Topamax, generic) may increase the risk for cleft palate or cleft lip when taken during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Drug Approval

In 2011, the FDA approved ezogabine (Potiga) for treatment of partial seizures in adults. Ezogabine is used in combination with other anti-epileptic medications.

.

Introduction

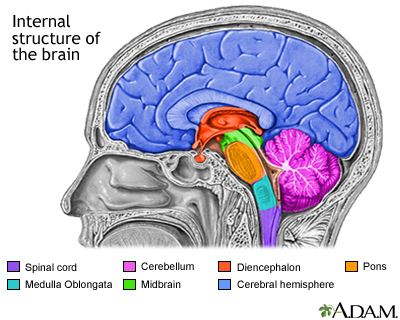

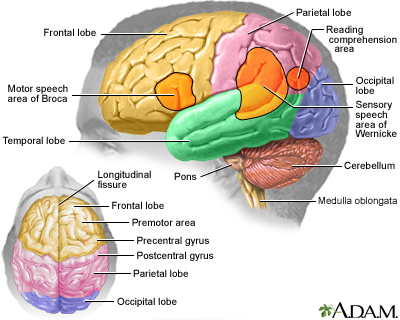

Epilepsy is a brain disorder involving repeated, spontaneous seizures of any type. There are different types of epilepsy but what they all share are recurrent seizures caused by an uncontrolled electrical discharge from nerve cells in the cerebral cortex. This part of the brain controls higher mental functions, general movement, the functions of the internal organs in the abdominal cavity, perception, and behavioral reactions.

Seizures

Seizures are a symptom of epilepsy. Seizures ("fits," convulsions) are episodes of disturbed brain function that cause changes in neuromuscular function, attention, or behavior. They are caused by abnormally excited electrical signals in the brain.

A single seizure may be related to a specific medical problem (such as brain tumor or withdrawal from alcohol). If repeated seizures do not recur after this underlying problem has been corrected, the person does not have epilepsy.

A single, first seizure that cannot be explained by a temporary medical problem has about a 25% chance of returning. After a second seizure occurs, there is about a 70% chance of future seizures and the diagnosis of epilepsy.

Types of Epilepsy

Epilepsy is generally classified into two main categories based on seizure type:

- Partial (also called focal or localized) seizures. These seizures are more common than generalized seizures and occur in one or more specific locations in the brain. In some cases, partial seizures can spread to wide regions of the brain. They are likely to develop from specific injuries, but in most cases the exact origins are unknown (idiopathic).

- Generalized seizures. These seizures typically occur in both sides of the brain. Many forms of these seizures are genetically based. There is usually normal neurologic function between episodes.

Partial Seizures (also called Focal Seizures)

These seizures are subcategorized as "simple" or "complex partial."

- Simple Partial Seizures. A person with a simple partial seizure (sometimes known as Jacksonian epilepsy) does not lose consciousness, but may experience confusion, jerking movements, tingling, or odd mental and emotional events. Such events may include deja vu, mild hallucinations, or extreme responses to smell and taste. After the seizure, the patient usually has temporary weakness in certain muscles. These seizures typically last about 90 seconds.

- Complex Partial Seizures. Slightly over half of seizures in adults are complex partial type. About 80% of these seizures originate in the temporal lobe, the part of the brain located close to the ear. Disturbances there can result in loss of judgment, involuntary or uncontrolled behavior, or even loss of consciousness. Patients may lose consciousness briefly and appear to others as motionless with a vacant stare. Emotions can be exaggerated; some patients even appear to be drunk. After a few seconds, a patient may begin to perform repetitive movements, such as chewing or smacking of lips. Episodes usually last no more than 2 minutes. They may occur infrequently, or as often as every day. A throbbing headache may follow a complex partial seizure.

In some cases, simple or complex partial seizures evolve into what are known as secondarily generalized seizures. The progression may be so rapid that the initial partial seizure is not even noticed.

Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures are caused by nerve cell disturbances that occur in more widespread areas of the brain than partial seizures. Therefore, they have a more serious effect on the patient. They are further subcategorized as tonic-clonic (or grand mal), absence (petit mal), myoclonic, or atonic seizures.

Tonic-Clonic (Grand Mal) Seizures. The first stage of a grand mal seizure is called the tonic phase, in which the muscles suddenly contract, causing the patient to fall and lie stiffly for about 10 - 30 seconds. Some people experience a premonition or aura before a grand mal seizure. Most, however, lose consciousness without warning. If the throat or larynx is affected, there may be a high-pitched musical sound (stridor) when the patient inhales. Spasms occur for about 30 seconds to 1 minute. Then the seizure enters the second phase, called the clonic phase. The muscles begin to alternate between relaxation and rigidity. After this phase, the patient may lose bowel or urinary control. The seizure usually lasts a total of 2 - 3 minutes, after which the patient remains unconscious for a while and then awakens to confusion and extreme fatigue. A severe throbbing headache similar to migraine may also follow the tonic-clonic phases.

Absence (Petit Mal) Seizures. Absence or petit mal seizures are brief losses of consciousness that occur for 3 - 30 seconds. Physical activity and loss of attention may pause for only a moment. Such seizures may pass unnoticed by others. Young children may simply appear to be staring or walking distractedly. Petit mal may be confused with simple or complex partial seizures, or even with attention deficit disorder. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #30: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.] In petit mal, however, a person may experience attacks as often as 50 - 100 times a day.

Myoclonic. Myoclonic seizures are a series of brief jerky contractions of specific muscle groups, such as the face or trunk.

Atonic (Akinetic) Seizures. A person who has an atonic (or akinetic) seizure loses muscle tone. Sometimes it may affect only one part of the body so that, for instance, the jaw slackens and the head drops. At other times, the whole body may lose muscle tone, and the person can suddenly fall. A brief atonic episode is known as a drop attack.

Simply Tonic or Clonic Seizures. Seizures can also be simply tonic or clonic. In tonic seizures, the muscles contract and consciousness is altered for about 10 seconds, but the seizures do not progress to the clonic or jerking phase. Clonic seizures, which are very rare, occur primarily in young children, who experience spasms of the muscles but not tonic rigidity.

Epilepsy Syndromes

Epilepsy is also grouped according to a set of common characteristics, including:

- Patient age

- Type of seizure or seizures

- Behavior during seizure

- Results of EEG recordings

- Whether a cause is known or not known (idiopathic)

A few syndromes and inherited epilepsies are listed discussed below; they do not represent all epilepsies.

Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Temporal lobe epilepsy is a form of partial (focal) epilepsy, although generalized tonic clonic seizures may occur with it.

Frontal Lobe Epilepsy. Frontal lobe epilepsy is characterized by sudden violent seizures. Seizures may also produce loss of muscle function, including the ability to talk. In autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, a rare inherited form, seizures often occur during sleep.

West Syndrome (Infantile Spasms). West syndrome, also called infantile spasms, is a disorder that involves spasms and developmental delay in children within the first year, usually in infants ages 4 - 8 months.

Benign Familial Neonatal Convulsions. Benign familial neonatal convulsions (BFNC) are a rare, inherited form of generalized seizures that occur in infancy. BFNC appears to be caused by genetic defects that affect channels in nerve cells that carry potassium.

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (Impulsive Petit Mal). Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, also called impulsive petit mal epilepsy, is characterized by generalized seizures, usually tonic-clonic marked by jerky movements (called myoclonic jerks), and sometimes absence seizures. It usually occurs in younger people ages 8 - 20.

Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is a severe form of epilepsy in young children that causes multiple seizures and some developmental retardation. It usually involves absence, tonic, and partial seizures.

Myoclonic-Astatic Epilepsy. Myoclonic-astatic epilepsy (MAE) is a combination of myoclonic seizures and astasia (a decrease or loss of muscular coordination), often resulting in the inability to sit or stand without aid.

Progressive Myoclonic Epilepsy. Progressive myoclonic epilepsy is a rare inherited disorder typically occurring in children ages 6 - 15. It usually involves tonic-clonic seizures and marked sensitivity to light flashes.

Landau-Kleffner Syndrome. Landau-Kleffner syndrome is a rare epileptic condition that typically affects children ages 3 - 7. It results in the loss of ability to communicate either with speech or by writing (aphasia).

Status Epilepticus

Status epilepticus (SE) is a serious, potentially life-threatening condition. It is a medical emergency. Permanent brain damage or death can result if the seizure is not treated effectively.

The condition is defined as recurrent convulsions that last for more than 30 minutes and are interrupted by only brief periods of partial relief. Although any type of seizure can be sustained or recurrent, the most serious form of status epilepticus is the generalized convulsive or tonic-clonic type. In some cases, status epilepticus occurs with the first seizure.

The trigger of status epilepticus is often unknown, but can include:

- Failure to take anti-epileptic medications

- Abrupt withdrawal of certain anti-epileptic drugs, particularly barbiturates and benzodiazepines

- High fever

- Poisoning

- Electrolyte imbalances (imbalance in calcium, sodium, and potassium)

- Cardiac arrest

- Stroke

- Low blood sugar in people with diabetes

- Central nervous system infection

- Brain tumor

- Alcohol withdrawal

Nonepileptic Seizures

A seizure may be related to temporary conditions listed below. If the seizures do not recur after the underlying problem has been corrected, the person does not have epilepsy.

Conditions associated with nonepileptic seizures include:

- Brain tumors, both in children and adults

- Other structural brain lesions (such as bleeding in the brain)

- Traumatic brain injury, stroke, or a transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Stopping alcohol after drinking heavily on most days

- Illnesses that cause the brain to deteriorate

- Problems that are present from before birth (congenital brain defects)

- Injuries to the brain that occur during labor or at the time of birth

- Low blood sugar or low sodium levels in the blood, or imbalances in calcium or magnesium

- Kidney or liver failure

- Infections (brain abscess, meningitis, encephalitis, neurosyphilis, or AIDS)

- Use of cocaine, amphetamines, or certain other recreational drugs

- Medications such as theophylline, meperidine, tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, lidocaine, quinolones, penicillins, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, isoniazid, antihistamines, cyclosporine, interferons, and lithium

- Stopping certain drugs, such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and certain antidepressants after taking them for a period of time

- Prolonged exposure to certain types of chemicals (lead, carbon monoxide).

- Down’s syndrome and other developmental conditions

- Phenylketonuria (PKU), a genetic disorder of metabolism, can cause seizures in infants

- Febrile seizures are convulsions in children triggered by a high fever. Most febrile seizures occur in young children ages 9 months to 5 years. Simple febrile seizures last for less than 15 minutes and only occur once in a 24-hour period. They are usually an isolated event and not a sign of underlying epilepsy. However, complex febrile seizures, which last longer than 15 minutes and occur more than once in 24 hours, may be a sign of underlying neurologic problems or epilepsy.

Causes

Epileptic seizures are triggered by abnormalities in the brain that cause a group of nerve cells in the cerebral cortex (gray matter) to become activated simultaneously, emitting sudden and excessive bursts of electrical energy. A seizure's effect depends in part on the location in the brain where this electrical hyperactivity occurs. Effects range from brief moments of confusion to minor spasms to loss of consciousness. In most cases of epilepsy, the cause is unknown (also called idiopathic).

Brain Chemistry Factors

Ion Channels. Sodium, potassium, and calcium act as ions in the brain. They produce electric charges that must fire regularly in order for a steady current to pass from one nerve cell in the brain to another. If the ion channels that carry them are genetically damaged, a chemical imbalance occurs. This can cause nerve signals to misfire, leading to seizures. Abnormalities in the ion channels are believed to be responsible for absence and many other generalized seizures.

Neurotransmitters. Abnormalities may occur in neurotransmitters, the chemicals that act as messengers between nerve cells. Three neurotransmitters are of particular interest:

- Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), which helps prevent nerve cells from over-firing.

- Serotonin's role in epilepsy is also being studied. Serotonin is a brain chemical that is important for well-being and associated behaviors (such as eating, relaxation, and sleep). Imbalances in serotonin are also associated with depression.

- Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter that is important for learning and memory.

Genetic Factors

Some types of epilepsy are inherited conditions where genetics play a factor. Generalized epilepsy seizure types appear to be more related to genetic influences than partial seizure epilepsies.

Injuries to the Brain

Head Trauma. Head injuries to adults can cause epilepsy in both adults and children, with the risk highest in severe head trauma. A first seizure related to the injury can occur years later, but only very rarely. People with mild head injuries that involve loss of consciousness for fewer than 30 minutes have only a slight risk that lasts up to 5 years after the injury.

Oxygen Deprivation. Cerebral palsy, and other disorders caused by lack of oxygen to the brain during birth, can cause seizures in newborns and infants.

Risk Factors

Epilepsy and seizure disorders affect nearly 3 million Americans and more than 45 million people worldwide.

Age

Epilepsy affects all age groups. The incidence is highest in children under the age of 2 and older adults over age 65. In infants and toddlers, prenatal factors and birth delivery problems are associated with epilepsy risk.

In children age 10 and younger, generalized seizures are more common. In older children, partial seizures are more common.

Gender

Males have a slightly higher risk than females of developing epilepsy.

Family History

People who have a family history of epilepsy are at increased risk of developing the condition.

Complications

Injuries and Accidents

Injuries from Falls. Because many people with seizures fall, injuries are common. Although such injuries are usually minor, people with epilepsy have a higher incidence of fractures than those without the disorder. Patients who take the drug phenytoin have an even higher risk, since the drug can cause osteoporosis.

Household Accidents. Household environments, such as the kitchen and bathroom, can be dangerous places for children with epilepsy. Parents should take precautions to prevent burning accidents from stoves and other heat sources. Children with epilepsy should never be left alone when bathing.

Driving and the Risk for Accidents. People with epilepsy who have seizures that are not controlled by medication are legally restricted from driving. In general, to obtain a driver's license, a doctor must confirm that a patient has been seizure-free for 3 - 6 months. Needless to say, seizures can be very dangerous if they occur while a person is driving and result in injuries to the patient or others.

Accidents while Swimming. Swimming poses another danger for people with epilepsy, particularly those with tonic seizures, which can cause the diaphragm to suddenly expel air. People with epilepsy who swim should avoid deep and cloudy water (a clear swimming pool is best), and always swim with a knowledgeable, competent, and experienced companion or have a lifeguard on site.

Effects of Epilepsy in Children

Long-Term General Effects. Long-term effects of seizures vary widely depending on the seizure's cause. The long-term outlook for children with idiopathic epilepsy (epilepsy of unknown causes) is very favorable.

Children whose epilepsy is a result of a specific condition (for example, a head injury or neurologic disorder) have lower survival rates, but this is most often due to the underlying condition, not the epilepsy itself.

Effect on Memory and Learning. The effects of seizures on memory and learning vary widely and depend on many factors. In general, the earlier a child has seizures and the more extensive the area of the brain affected, the poorer the outcome. Children with seizures that are not well-controlled are at higher risk for intellectual decline.

Social and Behavioral Consequences. Learning and language problems, and emotional and behavioral disorders, can occur in some children. Whether these problems are caused by the seizure disorder and anti-seizure medications or are simply part of the seizure disorder remains unclear.

Effects of Epilepsy in Adults

Psychological Health. People with epilepsy have a higher risk for suicide, particularly in the first 6 months following diagnosis. The risk for suicide is highest among people who have epilepsy and an accompanying psychiatric condition, such as depression, anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, or chronic alcohol use. All antiepileptic drugs can increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior. [For more information, see Medications section in this report.]

Overall Health. Patients with epilepsy often describe their overall health as "fair" or "poor," compared to those who do not have epilepsy. People with epilepsy also report more pain, depression, anxiety, and sleep problems. In fact, their overall health state is comparable to people with other chronic diseases, including arthritis, heart problems, diabetes, and cancer. Treatments can cause considerable physical effects, such as osteoporosis and weight changes.

Effect on Sexual and Reproductive Health

Effects on Sexual Function. Some patients with epilepsy experience sexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction. These problems may be caused by emotional factors, medication, or a result of changes in hormone levels.

Effects on Reproductive Health. A woman’s hormonal fluctuation can affect the course of her seizures. Estrogen appears to increase seizure activity, and progesterone reduces it. Antiseizure medications may reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptives.

Epilepsy can pose risks both to a pregnant woman and her fetus. Some types of anti-epileptic drugs should not be taken during the first trimester because they can cause birth defects. Women with epilepsy who are thinking of becoming pregnant should talk to their doctors in advance to plan changes in their medication regimen. Women should learn about the risks associated with epilepsy and pregnancy, and precautions that can be taken to reduce them. [For more information, see “Treatment during Pregnancy” in Treatment section of this report.]

Prognosis

Patients whose epilepsy is well controlled generally have a normal lifespan. However, long-term survival rates are lower than average if medications or surgery fail to stop the seizures. The lower survival rate is partly due to a higher-than-average risk for death due to accidents and suicide. The specific cause of the seizure may also contribute to fatalities.

Although relatively rare, there is a risk for sudden unexpected death in patients with epilepsy, a syndrome abbreviated as SUDEP. Although the causes of such events are not fully known, heart arrhythmias and pauses in breathing (apnea) may be factors in many cases. Your doctor can explain if you have specific risk factors for SUDEP and what protective measures can be taken.

The best preventive measure is to take your medication as prescribed. Talk with your doctor if you have any concerns about medication side effects or dosages. Do not make any changes to your drug regimen without speaking first with your doctor.

Diagnosis

An epilepsy diagnosis is often made during an emergency visit for a seizure. If a person seeks medical help for a previous or suspected seizure, the doctor will ask about the patient's medical history, including seizure events.

Diagnostic Tools

Electroencephalogram (EEG). The most important diagnostic tool for epilepsy is an EEG, which records and measures brain waves. Ideally, it should be performed within 24 hours of a seizure. An EEG recording session may last for less than an hour, but in some cases the doctor will want a day-long recording or a recording during sleep. Long-term monitoring may be necessary when patients do not respond to medications. Portable EEG units are available in some places, which can be used to monitor patients throughout normal activities. EEGs are not foolproof. Repeated EEGs are often needed to confirm a diagnosis, particularly for certain partial seizures that often produce an initially normal EEG reading.

Video Electroencephalography (Video EEG). For this test, patients are admitted to a special part of the hospital where they are monitored both by EEG and are also watched by a video camera. Patients may need to undergo video EEG monitoring for a variety of reasons including withdrawal or addition of medications in a patient with difficult-to treat-epilepsy, before epilepsy surgery for some patients, and also when nonepileptic seizures are suspected.

Computerized Tomography (CT) Scans. A CT scan is usually the initial brain imaging test ordered for most adults and children with first-time seizures. This imaging technique is sensitive enough for most purposes. In children, even if the scan is normal, the doctor will follow up to be sure other problems are not present.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Doctors strongly recommend MRIs for children with first seizures who are younger than age 1 year or who have seizures that are associated with any unexplained significant mental or motor problems. MRI scans may help to determine if the disorder can be treated with surgery, and may be used as a guide for surgeons.

Other Advanced Imaging Techniques. Some research centers use other types of imaging techniques. Positron emission tomography (PET) may help locate damaged or scarred locations in the brain where partial seizures are triggered. These findings may help determine which patients with severe epilepsy are good candidates for surgery. Single-photon emission computer tomography (SPECT) may also be used to decide if the surgery should be performed and what part of the brain needs to be removed. Both of these imaging techniques are generally only needed when an MRI of the brain has not been helpful.

Ruling Out Other Conditions

Conditions that may cause symptoms similar to epilepsy include:

- Syncope. Syncope (fainting), a brief lapse of consciousness, in which blood flow to the brain is temporarily reduced, can mimic epilepsy. It is often misdiagnosed as a seizure. Patients with syncope do not have the rhythmic contracting and then relaxing of the body's muscles.

- Migraines. Migraine headaches, particularly migraine with auras, may sometimes be confused with seizures. With epileptic seizure, the preceding aura is often seen as multiple, brightly colored, circular spots, while migraine sufferers tend to see black, white, or colorless lined or zigzag flickering patterns. Typically the migraine pain expands gradually over minutes to encompass one side of the head.

- Panic Attacks. In some patients, partial seizures may resemble a panic disorder. Symptoms of panic disorder include palpitations, sweating, trembling, sensation of breathlessness, chest pain, feeling of choking, nausea, faintness, chills or flushes, fear of losing control, and fear of dying.

- Narcolepsy. Narcolepsy, a sleep disorder that causes a sudden loss of muscle tone and excessive daytime sleepiness, can be confused with epilepsy.

Treatment

What To Do When Someone Has a Seizure

You cannot stop a seizure, but you can help the patient prevent serious injury.

Remain calm, and do not panic, then take the following actions:

- Wipe away any excess saliva to prevent obstruction of the airway. Do not put anything in the patient's mouth. It is not true that people having seizures will swallow their tongues.

- Turn the patient gently on the side. Do not try to hold the patient down to prevent shaking.

- Rest the patient's head on something flat and soft to protect it from banging on the floor and to support the neck.

- Move sharp objects out of the way to prevent injury.

Do not leave the patient alone. Someone nearby should call 911. Patients should be taken to an emergency room when:

- A first-time seizure occurs

- Any seizure lasts beyond 2 - 3 minutes

- The patient has been injured

- The patient is pregnant

- The patient has diabetes

- Parents, caregivers, or bystanders are at all uncertain

Not all patients with chronic epilepsy need to go to the hospital after a seizure. Hospitalization may not be necessary for patients whose seizures are not severe or repetitive, and who have no risk factors for complications. All patients or caregivers, however, should contact their doctors after a seizure occurs.

Starting Drug Treatment

Treatment with anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) is usually initiated or strongly considered for the following patients:

- Children and adults who have had two or three seizures. (If there was either a long period of time between seizures or the seizure was provoked by an injury or other specific causes, the doctor may wait before starting AEDs. In children, risk for recurrence after a single unprovoked seizure is rare. The risk after a second seizure is also low, even when the seizure is prolonged.)

- Children and adults after a single seizure if tests (EEG or MRI) reveal any brain injury, or if specific neurologic, developmental, or epilepsy syndromes put a person at special risk for recurrence, for instance, in cases of myoclonic epilepsy.

There is some debate about whether to treat every adult patient with an AED after a single initial seizure. Some doctors do not recommend treating adult patients after a single seizure if they have a normal neurologic examination, EEG, and imaging studies.

Determining an Anti-Epileptic Drug (AED) Regimen

Epileptic seizures can often be controlled using a single-drug regimen. First-line AED drugs include phenytoin (Dilantin, generic), carbamazepine (Tegretol, generic), and divalproex sodium (Depakote, generic). Patients generally begin with low doses and build up to higher doses until the seizures are controlled or a toxic reaction occurs. If a single drug fails to control seizures, other drugs are added on. The specific drugs and whether more than one should be used are determined by various factors, including the patient's age and the seizure type, frequency, and cause.

Monitoring Effects

During the first few months of therapy, the doctor will probably order blood tests once or twice to monitor drug levels and, if necessary, adjust dosages. Monitoring is used to check for AED complications, and to be sure the patient is complying with the regimen. These blood tests may be, however, a less reliable indicator of problems than patients’ own observations of response to the drug. For instance, blood tests may suggest that the dosage levels are insufficient according to general standards, yet the individual patient may be seizure-free and leading a normal life.

Anti-epileptic drugs interact with many other drugs, and may cause special problems in older patients who use multiple medications for other health problems. Elderly patients should have liver and kidney function tests performed before starting antiseizure medication. It is also very important that women have AED levels monitored during pregnancy (see "Treatment During Pregnancy" below).

Discontinuing Drug Therapy

Most patients who have responded well to medications can stop taking AEDs within 5 - 10 years. Evidence suggests that medications in children should not be halted for at least 2 years after the last seizure, particularly if they have partial seizures and abnormal EEGs. It is not clear whether children who have been free of generalized seizures need to wait more than 2 years or if they can withdraw earlier.

Treatment During Pregnancy

Preparing to Become Pregnant. Women with epilepsy who are considering pregnancy should talk to their doctors before they become pregnant. According to guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society:

- A woman who has been seizure-free for at least 9 months before becoming pregnant has a good chance of remaining seizure free during pregnancy.

- Folic acid is recommended for all pregnant women. Women with epilepsy should talk with their doctors about taking folic acid supplements at least 3 months before conception as well as during the pregnancy.

- Women with epilepsy do not face a substantially increased risk of premature birth or labor and delivery complications (including cesarean section). However, women with epilepsy who smoke may face a higher risk of premature delivery than women without epilepsy who smoke.

- Babies born to mothers who use an AED during pregnancy may be at increased risk of being small for their gestational age.

Medication Use During Pregnancy. Women should discuss with their doctors the risks of anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) and the possibility of making any changes in their drug regimen in terms of dosages or prescriptions. According to current guidelines:

- Women with epilepsy should consider taking only one AED during their pregnancy to reduce the risk of birth defects. Taking more than one AED may increase birth defect risk. Carbamazepine is generally considered to be the safest AED for use during pregnancy.

- Of all AEDs, valproate carries the highest risk for birth defects and should be avoided, if possible, during the first trimester. Valproate use has been associated with neural tube defects, facial clefts (cleft lip or palate), and hypospadias (abnormal position of urinary opening on the penis). Valproate may cause poor cognitive outcomes in children exposed to it in the womb. In studies, children born to mothers who took valproate during pregnancy had lower scores on IQ and other cognitive tests than children whose mothers took other types of AEDs. Women who take valproate during childbearing years should be sure to use effective birth control.

- Phenytoin and phenobarbital may also cause cognitive impairment.

- Topiramate (Topamax, generic) may increase the risk for cleft lip or palate birth defects when taken during the first trimester of pregnancy.

- Pregnancy can affect how an AED is metabolized in your body. AED levels tend to drop during pregnancy. Your doctor should monitor your blood levels throughout your pregnancy to see if your dosage needs to be adjusted. This is especially important if you take lamotrigine, carbamazepine, or phenytoin.

Breastfeeding. If women on AEDs breastfeed they should be aware that some types of AEDs are more likely than others to pass into the breast milk. The following AEDs appear to be the most likely to pass into breast milk in clinically important amounts: Primidone, levetiracetam, and possibly gabapentin, lamotrigine, and topiramate. Valproate does pass into breast milk, but it is unclear if it affects the nursing infant. A mother should watch for signs of lethargy or extreme sleepiness in her infant, which could be caused by her medication. Talk with your doctor about any concerns you have about breastfeeding and AEDs.

Medications

Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) include many types of medications but all act as anticonvulsants. Many newer AEDs are better tolerated than the older, standard AEDs, although they can still have troublesome side effects. Newer AEDs often cause less sedation and require less monitoring than older drugs. Although newer AEDs are generally FDA-approved for use as add-ons to standard drugs that have failed to control seizures, they are often prescribed as single drugs. Specific choices usually depend on the patient’s particular condition and the specific side effects of the AED.

All antiepileptic drugs can increase the risks of suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality). Research has shown that the highest risk of suicide can occur as soon as 1 week after beginning drug treatment and can continue for at least 24 weeks. Patients who take these drugs should be monitored for signs of depression, changes in behavior, or suicidality.

Valproate

Valproate sodium (Depacon, generic), valproic acid (Depakene, generic), and divalproex sodium (Depakote, generic) are anticonvulsants that are chemically very similar to each other. (In this report, they are referred to together as valproate.) Valproate products are the most widely prescribed anti-epileptic drugs worldwide. They are the first choice for patients with generalized seizures and are used to prevent nearly all other major seizures as well.

Side Effects. These drugs have a number of side effects that vary depending on dosage and duration. Most side effects occur early in therapy and then subside. The most common side effects are upset stomach and weight gain. Less common side effects include dizziness, hair thinning and loss, and difficulty concentrating.

Serious side effects include:

- A higher risk for serious birth defects than other AEDs especially if taken during the first trimester of pregnancy. In particular, these drugs are associated with facial cleft deformities (cleft lip or palate) and cognitive impairment. [See "Treatment During Pregnancy" in Treatment section.]

- Liver damage or failure is a rare but extremely dangerous side effect that usually affects children under 2 years of age who have birth defects and are taking more than one antiseizure drug.

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) and kidney problems are also rare but serious side effects.

Carbamazepine

Carbamazepine (Tegretol, Equetro, Carbatrol, generic) is used for many types of epilepsy. It is taken alone or in combination with other drugs. In addition to controlling seizures, it may help relieve depression and improve alertness. A chewable form is available for children.

Side Effects. Different side effects may develop or resolve at different points during treatment. Initial side effects may include:

- Double vision, headache, sleepiness, dizziness, and stomach upset. These usually subside after a week and can be greatly reduced by starting with a small dose and building up gradually.

- Some people experience visual disturbances, ringing in the ears, agitation, or odd movements when drug levels are at their peak. The extended-release form of carbamazepine (Carbatrol) may help reduce these symptoms.

Serious side effects are less common but can include:

- Skin reactions, including toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, so severe the drug has to be discontinued develop in about 6% of patients. These skin reactions cause skin lesions, blisters, fever, itching, and other symptoms. People of Asian ancestry have a 10 times greater risk for skin reactions than other ethnicities.

- A decrease in white blood cells occurs in about 10% of those taking the drug. This is generally not serious unless infection accompanies it.

- Other blood conditions can arise that are also potentially serious. Patients should be sure to inform their doctors if they have any sign of irregular heartbeats, sore throat, fever, easy bruising, or unusual bleeding.

- Long-term therapy can cause bone density loss (osteoporosis) in women, who should take preventive calcium and vitamin D supplements to improve bone mass.

- Children are at higher risk for behavioral problems.

Note: Citrus fruit, especially grapefruit, can increase carbamazepine's adverse effects.

Phenytoin

Phenytoin (Dilantin, generic) is effective for adults who have the following seizures or conditions:

- Grand mal seizures

- Partial seizures

- Status epilepticus

- Can be effective for people with head injuries who are at high risk for seizures

This drug is not useful for the following seizures:

- Petit mal seizures

- Myoclonic seizures

- Atonic seizures

Side Effects. Side effects are sometimes difficult to control. Some people may develop a toxic response to normal doses, while others may require higher doses to achieve benefits. As with any drug, side effects generally depend on dosage and duration. Side effects may include:

- Excess body hair, eruptions and coarsening of the skin, and weight loss

- Gum disease

- Staggering, lethargy, nausea, depression, eye-muscle problems, anemia, and an increase in seizures can occur as a result of excessive doses.

- Liver damage may develop in rare cases.

- Bone density loss from long-term therapy. Patients should take preventive calcium and vitamin D supplements and exercise regularly to improve bone mass.

- Severe and even rare life-threatening skin reactions (Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidemral necrosis)

- A possible increased risk for birth defects (cleft palate, poor thinking skills)

Barbiturates (Phenobarbital and Primidone)

Phenobarbital (Luminal, generic), also called phenobaritone, is a barbiturate anticonvulsant. Primidone (Mysoline, generic) is converted in the body to phenobarbital, and has the same benefits and adverse effects.

Barbiturates may be used to prevent grand mal (tonic-clonic) seizures or partial seizures. They are no longer typically used as first-line drugs, although they may be the initial drug prescribed for newborns and young children.

Side Effects. Phenobarbital has fewer toxic effects on other parts of the body than most anti-epileptic drugs, and drug dependence is rare, given the low doses used for treating epilepsy. Nevertheless, many patients experience difficulty with side effects.

Patients sometimes describe their state as "zombie-like." The most common and troublesome side effects are:

- Drowsiness

- Memory problems

- Problems with tasks requiring sustained performance

- Problems with motor skills

- Hyperactivity in some patients, particularly in children and the elderly

- Depression in some adults

When taken during pregnancy, phenobarbital, like phenytoin and valproate, may lead to impaired cognitive function in the child. There has been some evidence that phenobarbitol may cause heart problems in the fetus.

Ethosuximide and Similar Drugs

Ethosuximide (Zarontin, generic) is used for petit mal (absence) seizures in children and adults when the patient has experienced no other type of seizures. Methsuximide (Celontin), a drug similar to ethosuximide, may be suitable as an add-on treatment for intractable epilepsy in children.

Side Effects. This drug can cause stomach problems, dizziness, loss of coordination, and lethargy. In rare cases, it may cause severe and even fatal blood abnormalities. Periodic blood counts are recommended for patients taking this drug.

Clonazepam

Clonazepam (Klonopin, generic) is recommended for myoclonic and atonic seizures that cannot be controlled by other drugs and for Lennox-Gastaut epilepsy syndrome. Although clonazepam can prevent generalized or partial seizures, patients generally develop tolerance to the drug, which causes seizures to recur.

Side Effects. People who have had liver disease or acute angle glaucoma should not take clonazepam, and people with lung problems should use the drug with caution. Clonazepam can be addictive, and abrupt withdrawal may trigger status epilepticus. Side effects include drowsiness, imbalance and staggering, irritability, aggression, hyperactivity in children, weight gain, eye muscle problems, slurred speech, tremors, skin problems, and stomach problems.

Lamotrigine

Lamotrigine (Lamictal, generic) is approved as add-on (adjunctive) therapy for partial seizures, and generalized seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, in children aged 2 years and older and in adults. Lamotrigine is also approved as add-on therapy for treatment of primary generalized tonic-clonic (PGTC) seizures, also known as “grand mal” seizures, in children aged 2 years and older and adults. Lamotrigine can be used as a single drug treatment (monotherapy) for adults with partial seizures. Birth control pills lower blood levels of lamotrigine.

Side Effects. Common side effects include dizziness, headache, blurred or double vision, lack of coordination, sleepiness, nausea, vomiting, insomnia, and rash. Although most cases of rash are mild, in rare cases the rash can become very severe. The risk of rash increases if the drug is started at too high a dose or if the patient is also taking valproate. (Serious rash is more common in young children who take the drug than it is in adults.) Rash is most likely to develop within the first 8 weeks of treatment. Be sure to immediately notify your doctor if you develop a rash, even if it is mild.

Lamotrigine may cause aseptic meningitis. Symptoms of meningitis may include headache, fever, stiff neck, nausea, vomiting, rash, and sensitivity to light. Patients who take lamotrigine should immediately contact their doctors if they experience any of these symptoms.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin (Neurontin, generic) is an add-on drug for controlling complex partial seizures and generalized partial seizures in both adults and children.

Side Effects. Side effects include sleepiness, headache, fatigue, and dizziness. Some weight gain may occur. Children may experience hyperactivity or aggressive behavior. Long-term adverse effects are still unknown.

Pregabalin

Pregabalin (Lyrica) is similar to gabapentin.It is approved as add-on therapy to treat partial-onset seizures in adults with epilepsy.

Side Effects. Dizziness, sleepiness, dry mouth, swelling in hands and feet, blurred vision, weight gain, and trouble concentrating may occur.

Topiramate

Topiramate (Topamax, generic) is similar to phenytoin and carbamazepine and is used to treat a wide variety of seizures in adults and children. It is approved as add-on therapy for patients 2 years and older with generalized tonic-clonic seizures, partial-onset seizures, or seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. It is also approved as single drug therapy.

Side Effects. Most side effects are mild to moderate and can be reduced or prevented by beginning at low doses and increasing dosage gradually. Common side effects may include numbness and tingling, fatigue, abnormalities of taste , difficulty concentrating, and weight loss. Serious side effects may include glaucoma and other eye problems. Tell your doctor right away if you have blurred vision or eye pain. If used during pregnancy, topiramate can increase the risk for cleft lip or palate birth defects.

Oxcarbazepine

Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal, generic) is similar to phenytoin and carbamazepine but generally has fewer side effects. It is approved as single or add-on therapy for partial seizures in adults and for children ages 4 years and older.

Side Effects. Serious side effects, while rare, include Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. These skin reactions cause a severe rash that can be life threatening. Rash and fever may also be a sign of multi-organ hypersensitivity, another serious side effect associated with this drug. Oxcarbazepine can reduce sodium levels (hyponatremia). Your doctor may want to monitor the sodium (salt) level in your blood. This drug can reduce the effectiveness of birth control pills. Women who take oxcarbazepine may need to use a different type of contraceptive.

Zonisamide

Zonisamide (Zonegran, generic) is approved as add-on therapy for adults with partial seizures.

Side Effects. Zonisamide increases the risk for kidney stones. It may reduce sweating and cause a sudden rise in body temperature, especially in hot weather. Other side effects tend to decrease over time and may include dizziness, forgetfulness, headache, weight loss, and nausea.

Levetiracetam

Levetiracetam (Keppra, generic) is approved both in oral and intravenous forms as add-on therapy for treating many types of seizures in both children and adults.

Side Effects. These tend to occur mostly in the first month. They include sleepiness, dizziness, and fatigue. More serious side effects may include muscle weakness and coordination difficulties, behavioral changes, and increased risk of infections.

Tiagabine

Tiagabine (Gabitril) has properties similar to phenytoin and carbamazepine.

Side Effects. Tiagabine may cause significant side effects including dizziness, fatigue, agitation, and tremor. The FDA has warned that tiagabine may cause seizures in patients without epilepsy. Tiagabine is only approved for use with other anti-epilepsy medicines to treat partial seizures in adults and children 12 years and older

Ezogabine

Ezogabine (Potiga), a potassium channel opener, was approved in 2011 for treatment of partial seizures in adults. Ezogabine is used as an add-on (adjunctive) medication. Its most serious side effect is urinary retention. Patients should be monitored for symptoms such as difficulty initiating urination, weak urine stream, or painful urination. Other side effects may include coordination problems, memory problems, fatigue, dizziness, and double vision.

Less Commonly Used AEDs

Felbamate. Felbamate (Felbatol) is an effective antiseizure drug. However, due to reports of deaths from liver failure and from a serious blood condition known as aplastic anemia, felbamate is recommended only under certain circumstances. They include severe epilepsy, such as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, or as monotherapy for partial seizures in adults when other drugs fail.

Vigabatrin. Vigabatrin (Sabril) has serious side effects and is generally prescribed only in certain cases, such as in low doses for patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Between 10 - 30% of people on long-term treatment have developed irreversible visual disturbances, including reductions in acuity and color vision.

In 2009, vigabatrin became the first drug approved in the U.S. to treat infantile spasms in children ages 1 month to 2 years. For infantile spasm treatment, it is given as a low-dose oral solution.

Surgery

Surgical techniques to remove injured brain tissue may be appropriate for some patients with epilepsy. The surgeon's goal is to remove only the damaged tissue to prevent seizures and to avoid removing healthy brain tissue. The goal is to eliminate or at least reduce seizure activity while not causing any functional deficits, such as deterioration of speech or cognitive abilities.

Surgical techniques and pre-surgical planning for reaching these goals have improved significantly over the past decades due to advances in imaging and monitoring, new surgical techniques, and a better understanding of the brain and epilepsy.

Evaluation to Determine Best Surgical Candidates

A number of tests using imaging and electroencephalography (EEG) can determine if surgery is an option:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans may identify an abnormality in brain tissue that is causing poorly controlled seizures.

- Ambulatory EEG monitoring involves wearing an EEG while taking part in everyday life. Video EEG monitoring involves being admitted to a special unit in the hospital and being observed while seizures occur. These tests are done to help locate the exact brain tissue that is triggering the epileptic event.

- Advanced imaging techniques can sometimes provide valuable additional information. They include functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), or single-photon emission computer tomography (SPECT) scans.

If the imaging tests indicate that more than one site is involved or their results conflict, then more invasive monitoring of the brain may be required, although the newer imaging tests are proving to be very accurate tools. If such tests pinpoint a specific area in the brain as the location for seizures, surgery is possible. The doctor will also examine the test results to avoid damaging areas of the brain necessary for the performance of vital functions.

While it is important to identify patients who are most likely to have successful outcomes from a medical standpoint, it is also important to identify a patient’s suitability for surgery based on psychosocial factors. Patients who have significant psychiatric disorders, or a history of not following prescribed medical treatment, may not be suitable candidates.

Anterior Temporal Lobectomy

The most common surgical procedure for epilepsy is anterior temporal lobectomy, which is performed when seizure originate in the area of the temporal lobe. (Surgery is not as successful in epilepsies that occur in the frontal lobe.) It involves removing the front portion of the temporal lobe and small portions from the hippocampus. The hippocampus is contained in the temporal lobe and is a part of the brain that is involved in memory processing. It is part of the limbic system, which controls emotions.

Candidates for this surgery usually have a history of seizures that have not been helped by anti-epileptic drugs. Temporal lobe surgery successfully reduces or eliminates seizures in about 60 – 80% patients within 1 -2 years following surgery. Patients may still need to take medications after surgery, even if seizures are very infrequent.

Lesionectomy

Lesionectomy is a procedure that is performed to remove a lesion in the brain. Brain lesions are damaged or abnormal tissues that may be caused by:

- Cavernous angiomas (abnormal clusters of blood vessels)

- Low-grade brain tumors

- Cortical dysplasias (these are a type of birth defect in which the normal migration of nerve cells is altered)

Lesionectomy may be appropriate for patients whose epilepsy has been identified as associated with a defined lesion and whose seizures are not well controlled by medication.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

Electrical stimulation of areas in the brain that affect epilepsy can help many patients with refractory epilepsy. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), an electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve, is now an accepted therapy for severe epilepsy that does not respond to AEDs. The two vagus nerves are the longest nerves in the body. They run along each side of the neck, then down the esophagus to the gastrointestinal tract. They affect swallowing, speech, and many other functions. They also appear to connect to parts of the brain that are involved with seizures. The VNS procedure is as follows:

- A battery-powered device similar to a pacemaker is implanted under the skin in the upper left of the chest.

- A lead is then attached to the left vagus nerve in the lower part of the neck.

- The neurologist programs the device to deliver mild electrical stimulation to the vagus nerve. (Patients may also pass a magnet over the device to give it an extra dose if they sense a seizure coming on.)

- The batteries wear out after 3 - 5 years and need to be removed and replaced by a simple surgical procedure.

Candidates. The American Academy of Neurology recommends VNS for:

- Patients who are over 12 years old, and

- Have partial seizures that do not respond to medication, and

- Are not appropriate candidates for surgery

Evidence is accumulating, however, to indicate that VNS may be effective and safe for many patients of all ages and for refractory epilepsy of many types.

Success Rates. Studies report that the procedure reduces seizures within 4 months by up to 50% and even more in many patients.

Complications. Vagus nerve stimulation does not eliminate seizures in most patients and is still somewhat invasive. VNS can cause shortness of breath, hoarseness, sore throat, coughing, ear and throat pain, or nausea and vomiting. These side effects can be reduced or eliminated by reducing the intensity of stimulation. Some studies suggest that the treatment causes adverse changes in breathing during sleep and may cause lung function deterioration in people with existing lung disease. People who have obstructive sleep apnea should be cautious about this procedure. Turning off the VNS (for example before an MRI or surgery) may increase the risk for status epilepticus. (However, VNS may also be helpful for treating status epilepticus in some patients.)

Investigational Procedures

Deep Brain Stimulation. An investigational neurostimulation approach called deep brain stimulation (DBS) targets the thalamus, the part of the brain that produces most epileptic seizures. Early results have shown some benefit. Researchers are also studying other implanted brain and nerve stimulation devices such as the responsive neurostimulator system (RNS), which detects seizures and stops them by sending electrical stimulation to the brain. A third investigational approach, trigeminal nerve stimulation (TNS), stimulates a nerve involved in inhibiting seizures.

Stereotactic Radio Surgery. Focused beams of radiation are able to destroy lesions deep in the brain without the need for open surgery. Sometimes used for brain tumors, stereotactic radio surgery is also under investigation for temporal lobe epilepsy and for seizures due to cavernous malformations. It may be used for patients when an open surgical approach is not possible because the location of the abnormal area is surrounded by delicate brain tissue.

Lifestyle Changes

Seizures cannot be prevented by lifestyle changes alone, but people can make behavioral changes that improve their lives and give them a sense of control.

Avoiding Epileptic Triggers

In most cases, there is no known cause for epileptic seizures, but specific events or conditions may trigger them and should be avoided.

Poor Sleep. Inadequate or fragmented sleep can set off seizures in many people. Using sleep hygiene or other methods to improve sleep may be helpful.

Food Allergies. Food allergies may trigger seizures in children who also have migraine headaches, hyperactive behavior, or abdominal pains. Parents should consult an allergist if they suspect foods or additives might be playing a role in such cases.

Alcohol and Smoking. Alcohol and smoking should be avoided, although light alcohol consumption does not appear to increase seizure activity in people who are not alcohol dependent or sensitive to alcohol.

Flashing Lights. Patients should avoid exposure to flashing or strobe lights. Video games have been known to trigger seizures in people with existing epilepsy, but apparently only if they are already sensitive to flashing lights. Seizures have been reported among people who watch cartoons with rapidly fluctuating colors and quick flashes.

Relaxation Techniques

Relaxation methods include deep breathing, biofeedback, and meditation techniques. No strong evidence supports their value on reducing seizures (although some people benefit), but they may be helpful in reducing anxiety in some patients.

Exercise

Exercise is important for many aspects of epilepsy, although it can be problematic. Weight-bearing exercise helps maintain bone density, which can be reduced by many of the medications, particularly the older ones. Exercise can also help to prevent weight gain, which is a problem with some drugs. There have been some reports that exercise may trigger seizures in some patients, but this is uncommon. Several studies have found no significant association between physical activity and a higher incidence of seizures in patients with epilepsy. Nevertheless, if patients are concerned they should discuss this issue with their doctors.

Some small studies have reported significant benefits from the practice of yoga, which employs weight bearing and balancing postures. Well-controlled studies are needed to confirm these benefits.

Dietary Measures

All patients should maintain a healthy diet, including plenty of whole grains, fresh vegetables, and fruits. In addition, dairy foods may be important to maintain calcium levels.

Fasting has been used to prevent seizures since ancient times. In the 1920s, a high-fat, no-sugar, low-protein diet, known as a ketogenic diet, was used to prevent seizures. Researchers are investigating whether a modified version of the Atkins diet (high protein, low carbohydrate) may help people with epilepsy.

Both the ketogenic diet and the Atkins diet can interfere with some anti-epileptic medications, such as topiramate. Talk to your doctor before beginning any special diet or a weight loss program.

The Ketogenic Diet

The ketogenic diet -- which is very high in fat (90%), very low in carbohydrates, and low in protein -- has been studied and debated for decades. It has proven to be helpful for many children with severe epilepsy that does not respond to AEDs. It is not clear why it works. The standard theory is that burning fat instead of carbohydrates causes an increase in ketones (chemical substances in the body that result from the breakdown of fat in the body). When excessive levels of ketones are produced, a metabolic state called ketosis happens. Ketosis appears to alter certain amino acids in the brain and to increase levels of the neurotransmitter gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), which helps prevent nerve cells from over-firing.

Benefits. Studies report that about 10 - 15% of children who use the diet are seizure free after 1 year, while 30% are nearly seizure free. Some parents report that the diet helps improve their children’s alertness, even if seizures continue. Some children who try the ketogenic diet are able to stop or at least reduce their medications.

Typical Ketogenic Diet. (This diet must be professionally monitored! Parents can endanger their children if they try the program on their own without consulting a doctor or trained health expert.) The child fasts for the first 1 - 2 days, then the diet is gradually introduced. The regimen uses small amounts of carbohydrates and large amounts of fats (up to 90%), with very few proteins and no sugar. Children generally consume 75% of their usual daily calorie requirements.

A typical dinner may include a chicken cutlet or piece of fish, broccoli with cheese, lettuce with mayonnaise, and a whipped cream sundae. Vegetables may include celery, cucumbers, or asparagus, cauliflower, and spinach. Breakfast might consist of an omelet, bacon, and cocoa with cream. (Artificial sweeteners are used for any desserts.)

The diet is very complex and difficult, as a slight deviation from the diet can provoke a seizure. Children cannot take medications that contain sugar (which is common in many drugs produced for children). Some sunscreens and lotions contain sorbitol, a carbohydrate that can be absorbed through skin. About half of patients find the diet too difficult or ineffective and stop it after 6 months.

Researchers are also investigating a modified version of the popular Atkins diet, which does not require the caloric, protein, or fluid restrictions of the ketogenic diet. Unlike the traditional Atkins diet, the modified Atkins diet uses less carbohydrates and more fat intake. Early results indicate that it might be helpful for some patients with epilepsy. Another alternative is a low glycemic index diet, which contains even fewer carbohydrates than the Atkins diet. Still, parents should not put their children on these diets without support from a doctor.

Side Effects and Complications. To prevent serious side effects, children need regular monitoring by a doctor, especially when the ketogenic diet is first initiated.

Side effects or complications that may occur at the start of the diet include:

- Acidosis, a build-up of acid in the blood and body

- Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia)

- Stomach upset

- Dehydration

- Lethargy

Side effects that may occur later on include:

- Unhealthy cholesterol and lipid levels

- Vitamin and mineral deficiencies (patients need to take supplements)

- Kidney stones, which may be a complication of acidosis.

- Slowing of growth (tends to occur more in younger children than older children)

- Decreased bone density

Because most patients remain on the diet for only 2 years, the risks for potential long-term damage appear minimal.

Emotional and Psychologic Support

Many patients with epilepsy and parents whose children have epilepsy can benefit from support associations. These services are usually free and available in most cities.

Tips for Helping Children. Some of the following tips may help the child with epilepsy:

- Children should be treated as normally as possible by parents and siblings.

- Children should be assured that they will not die from epilepsy.

- Most children will not have seizures triggered by sports or by any other ordinary activities that are enjoyable and healthy.

- As soon as they are old enough, children should be active participants in maintaining their drug regimens, which should be presented in as positive a light as possible.

Therapies for Children and Adults. Because of the risks for serious emotional consequences, psychological therapy may be helpful. Cognitive behavioral therapy offers a structured counseling program that helps people change behaviors associated with seizure triggers, such as anxiety and insomnia.

Resources

- www.epilepsyfoundation.org -- Epilepsy Foundation

- www.aesnet.org -- American Epilepsy Society

- www.ninds.nih.gov -- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

References

Bell GS, Gaitatzis A, Bell CL, Johnson AL, Sander JW. Suicide in people with epilepsy: how great is the risk? Epilepsia. 2009 Aug;50(8):1933-42. Epub 2009 May 12.

Christensen J, Vestergaard M, Mortensen PB, Sidenius P, Agerbo E. Epilepsy and risk of suicide: a population-based case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2007 Aug;6(8):693-8.

Donner EJ. Explaining the unexplained; expecting the unexpected: where are we with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy? Epilepsy Curr. 2011 Mar;11(2):45-9.

Foldvary-Schaefer N, Wyllie E. Epilepsy. In: Goetz C, ed. Textbook of Clinical Neurology. 3rd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier. 2007:chap 52.

Freeman JM, Kossoff EH, Hartman AL. The ketogenic diet: one decade later. Pediatrics. 2007 Mar;119(3):535-43.

French JA, Pedley TA. Clinical practice. Initial management of epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul 10;359(2):166-76.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY, Pennell PB, French JA, Hauser WA, et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy--focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009 Jul 14;73(2):126-32. Epub 2009 Apr 27.

Harden CL, Meador KJ, Pennell PB, Hauser WA, Gronseth GS, French JA, et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy -- focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): teratogenesis and perinatal outcomes: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009 Jul 14;73(2):133-41. Epub 2009 Apr 27.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS, Hovinga CA, Gidal B, Meador KJ, et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy--focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009 Jul 14;73(2):142-9. Epub 2009 Apr 27.

Hirsch LJ, Donner EJ, So EL, Jacobs M, Nashef L, Noebels JL, et al. Abbreviated report of the NIH/NINDS workshop on sudden unexpected death in epilepsy. Neurology. 2011 May 31;76(22):1932-8. Epub 2011 May 4.

Johnson MV. Seizures in childhood. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:chap 586.

Kossoff EH, Zupec-Kania BA, Rho JM. Ketogenic diets: an update for child neurologists. J Child Neurol. 2009 Aug;24(8):979-88. Epub 2009 Jun 17.

Krumholz A, Wiebe S, Gronseth G, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure in adults (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2007 Nov 20;69(21):1996-2007.

Kwan P, Schachter SC, Brodie MJ. Drug-resistant epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2011 Sep 8;365(10):919-26.

Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, Clayton-Smith J, Combs-Cantrell DT, Cohen M, et al. Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 16;360(16):1597-605.

Mølgaard-Nielsen D, Hviid A. Newer-generation antiepileptic drugs and the risk of major birth defects. JAMA. 2011 May 18;305(19):1996-2002.

Salanova V, Worth R. Neurostimulators in epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007 Jul;7(4):315-9.

Schachter SC. Seizure disorders. Med Clin North Am. 2009 Mar;93(2):343-51, viii.

Trescher WH, Lesser RP. The epilepsies. In: Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel G, Jankovic, eds. Neurology in Clinical Practice. 5th ed. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann Elsevier. 2008:chap 71.

|

Review Date:

2/8/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |